Blog

AI in Video Production

Relatively speaking, AI video creation is in its infancy still with perhaps the most famous example being Sora AI Video Generator, which is an OpenAI video generator that garnered a lot of media attention for some of the creepy imagery spit out from user prompts. Despite strange faces, extra limbs, or almost surrealistic interpretations of user text prompts, AI video creation is only going to improve. For all of us in the film industry, the response is a mixture of curiosity and terror. Could AI threaten our livelihoods and replace our jobs? The knee-jerk reaction is to reject new technology if it could be a threat, but the wiser approach is to embrace new technology as merely tools in the creation of human-directed art and marketing videos. Ultimately, people connect with other people. Sure, maybe one day an AI video generator could spit out a 30 second Taco Bell commercial with all AI-created “humans” and no camera being involved at all, but even then, the commercial has to be specifically designed to appeal to consumers — actual humans, not AI creations.

At present, the best use for AI video creation tools is to make small clips used in larger, human-created projects or for throw-away social media engagement videos. For instance, platforms like Pictory.AI can take a script or article and turn it into an AI-generated video complete with stock footage, AI-generated voiceover, and text. With how SEO favors videos over text, there’s something to be said for throwing up easy-to-create AI videos of a press release or something along those lines instead of just a wall of text. The results are decidedly mixed, though, with a lot of the AI-generated results needing some massaging and manipulation to come across as useful marketing pieces.

moreVideo Production Packages

When considering your company’s video production needs, eventually the discussion arrives at which package will maximize your value and minimize the cost. Typically, video production companies offer a variety of “set” packages that include the number of hours of filming required, length of the deliverable video, crew involved in production, and even the equipment used for the project. On more sophisticated videos, package pricing becomes impossible because of the highly customized needs for the video such as casting, actors, locations, effects work, specialized gear such as a slow motion camera, underwater videography, or special permits for filming in sensitive locations (seaports, airports, freeways, etc.). Your job as the marketing expert is to figure out what you need from the video, then let the video production company help decide what package is right.

Basic Vs. Custom Video Packages

For our clients, we typically customize quotes based on our two basic packages, which are a half-day shoot and a full day shoot. From there, we can determine any additional needs though our typical full day shoot package is sufficient for the majority of our clients and includes every professional detail for a nice finished video. With custom video production packages, the price and what’s included is determined after careful discussions with the client figuring out the exact details of the video. For instance, the script or concept may dictate a location rental is needed, four actors have to be hired (thus a casting director involved), additional crew will be needed for higher end lighting and production, a makeup artist might be warranted, and an on-set director / producer to help make sure everyone is on the same page and the time is maximized to deliver a great finished video.

moreFinding an Austin Video Production Company

When searching for an Austin video production company, marketing professionals may want to consider a company that has filmed all over Texas in almost every city large and small, from car dealerships to senior living communities to airport terminals to logistics facilities, many of them in Austin. At JLB Media Productions, we believe in a specialized approach to video production that meshes an agency approach with the single owner-operator approach. With marketing agencies, video production is one service they offer, but is often highly marked up because of expensive office space, many employees, and generally high overhead. With single owner-operators, you’re asking one person to be the best possible videographer, the best editor, the best customer service representative, and the best marketing specialist. We believe in keeping our videos affordable to clients while still having a key professional to handle each aspect of the video creation process.

Our Fundamental Company Tenet

One of the fundamental company tenets is offering video production packages to our clients without travel costs. For many companies, they might be based in one city like Austin, but have a conference in Las Vegas or Chicago, or need a customer testimonial in New York, or they may even have properties spread across Texas and other states. We want to make sure that when we discuss pricing, our clients will pay the same price for the same type of video in another city, which is why we’ve spent more than a decade building a talented and trusted network of videographers. Many of our videographers have been shooting for us since early in the company’s history, some have changed markets and continued to work with us, and our strong bond with our production talent helps us assure quality videos time after time.

moreFinding a Chicago Production Company

Searching for a Chicago production company that can provide reasonable video production pricing and videography rates? JLB Media Productions has shot aircraft terminals, commercial office buildings for CBRE, senior apartments, assisted living communities, and worked with major Chicago-based companies like Grant Thornton to handle their video needs. Whether you’re looking for event video production, virtual tours, product demos, or even training videos, our team can assist you in creating the perfect video and ideal marketing asset. With new clients, our first priority is learning what purpose the video is intended to serve so that we can better tailor the video production pricing to meet their needs. We offer several standard package prices, but can design a custom quote for more sophisticated video needs.

Included in the discussion of target audience and delivery methods (social media, company channels, etc.) is figuring out how we can communicate your message in the most effective way using our decade-plus of experience in the industry. As a pioneer in online business-to-business video production, we have shot more than a thousand videos nationwide for clients in all industries from senior living to commercial real estate, technology to medical care, and financial services to logistics companies. Understanding your business and key marketing goals are top priorities for any serious film production company because ultimately video is a tool, used to drive traffic to your property, your Website, or to sell product, engage with customers, find potential customers, and elevate your bottom line.

more10 Tips for Corporate Video Production

- Come up with a general budget range you want to spend. You may not know exactly what to expect, but generally a professional video will range anywhere from $1,500 to $20,000, depending on a variety of factors. More documentary-style filmmaking (interviews with employees and executives, filming at the office or place of business, etc.) will be less expensive than hiring professional actors, a creative director, larger crew, and sophisticated post-production work.

- Find videos online that match the style, tone, or feeling you would like for your video. Maybe a competitor has a video that caught your eye, or maybe a TV commercial you saw has elements that you want to replicate. Whatever the case, finding a few sample videos to send to a video production company can be immensely helpful in communicating your vision.

- Know the audience for your corporate video production. Are you targeting consumers or other businesses? If you’re targeting other businesses, are you focused on their marketing staff? Their IT professionals? Their HR directors? If you’re targeting consumers, what is the profile of your average buyer? The video should generally appeal to the kind of person who is most likely to be interested in your product or service. By contrast, maybe you are trying to expand your marketshare and want to target a new demographic.

- Come up with a rough concept or outline for the video. You don’t need an exact script, but try to come up with the driving force or idea for the video. If you want a highly creative idea and need expert guidance, many production companies have a creative director who can help, but the cost will increase.

- Make sure the video production company you choose has experience producing similar quality videos. You don’t need to choose a production company that has done exactly the type of video you want in the same industry, but you need a company that creates work that matches your expectations. If a company primarily produces cheesy infomercials and you want a high-end video for an innovative tech product, you should keep searching for a better fit.

- Agree to a timeline with the video production company. Your marketing efforts may depend on having a completed, polished video by a certain date. Make sure the production company understands your deadline and agrees to finish on time or, ideally, early.

- Have a point of contact at your company to manage the video production. Although your company may have a handful of people who are involved in the creation of a marketing video, make sure one person takes the lead and communicates clearly with the video production company what is required. The point of contact should be there on the day or days of production making sure everything proceeds smoothly.

- Make sure you collect all release forms from the shoot. If the production company is using professional actors, request copies of the release forms that give your company permission to display their image and likeness on camera. If you are using your own staff or customer testimonials, make sure to collect your own release forms from everyone.

- Ask the production company to deliver a full quality master file. After paying a good chunk of money for a professional video, you should request any and all files you will need for future use, especially the master file.

- Have a plan for where you want to distribute the video. Will the video mainly live on the company home page? If so, you should still find ways to share it on social media outlets through the company channels, on your YouTube channel, and any partner sites that may be willing to share your video.

Creating Facebook 360 Videos for Marketing Purposes

One of the bigger video trends of 2016 — and one of the most fun — is Facebook allowing video postings of 360 videos often created by panoramic photos users generate. For instance, someone can create a 360 video while on a boat in the ocean off the coast of Hawaii and showcase their surroundings in a “wish you were here” type of posting. The videos are immersive and innovative, allowing iOS and Android mobile users to hold their phone up in the air and see a rotating 360 image by moving their phone in front of them. The experience is almost like a window into another world far away, made more realistic by the movement of the video mimicking the movement of the mobile device.

Not surprisingly, National Geographic has used the videos to great effect on their Facebook page to capture beautiful and far away places for their fan base to enjoy. Other companies can use them to engage with audiences, too, even if they can’t showcase the same amazing visuals. For instance, you may want to create a 360 video showcasing a new store display area, or a grand opening of a restaurant, or even a remodel of a local business. Though not necessarily a prime candidate for the production expertise of a corporate video production company, they can form a part of your overall video marketing goals.

moreVideo Request for Proposal Tips

Crafting a quality request for proposal for corporate video production is an essential element of obtaining accurate quotes from production companies. Many executives have experience creating RFPs, but video production requires a special set of considerations that may not come to mind immediately. The usual elements are still essential, like a target audience, basic messaging and product or service details, and details about what you want or expect to see in the video on a general level. Being unsure about many of the details is not a problem, but being unsure about both the budget and the details can create issues with production companies trying to offer accurate quotes. Here are some tips:

- Explain location considerations and needs. If you write, “Interviews with corporate executives,” make sure to include whether you imagine the interviews all taking place at one location or at numerous locations (even different cities?), and whether the location or locations are company-controlled or elsewhere. In other words, corporate offices are available and free, but if you imagine the interviews taking place atop a beautiful rooftop with a view of the city, the production company needs to plan for the costs accordingly. Public locations will also require pulling permits, which can cost varying amounts of money depending on the city and crew.

- Specify whether B-roll footage (for instance, shots of people working, activities, etc.) will use company employees or paid actors. The difference in cost can be immense, not just because of hiring the actors but also hiring a casting director or compensating a producer for the time spent hiring cast. Additionally, consider whether a professional makeup artist and hair stylist is needed for the shoot, or whether it’s an unnecessary expense.

- Think about any special shots you may want in the video. If you imagine aerial footage in your video, indicate roughly what types of shots would be needed. If you like time lapse footage, mention what type of time lapse you envision (city view, activities, a sunset, etc.).

- If props are involved, for instance in a training video or product video, explain whether you are providing them or the production company needs to provide them. If you want to picture someone driving, will the car be a company car? A personal car? Will the production company need to rent a car of a specific type?

- Think about licensed content and avoid requesting it unless your budget is high. If you want to use a famous song, it will be very expensive most likely. If you want to show video game footage or movie footage, clearance may be both expensive and time-consuming. Many times, a company is better off securing their own clearances rather than paying for the clearance and the markup that a production company will charge.

- Be detailed about any graphical elements. If you want your logo animated, indicate your desire on the RFP. If you imagine multiple segments of motion graphics, try to be clear about their rough length and details.

- As much as possible, always provide extreme detail. Instead of indicating, “Demonstration of product features,” write, “Employee holding the product and explaining its features with close-up shots, text reinforcement of messaging and benefits, and creative lighting.” The final detail lets the production company know you don’t want a down-and-dirty job, but glamour shots of the product.

If a Picture is Worth a Thousand Words, What is a Video Worth?

If a 30-second commercial is rendered at 30 frames per second, then based on the unscientific assessment that a picture is “worth a thousand words,” the commercial would be worth almost a million words! What is it that makes video such a valuable tool for communication, and why is it that it has such a significant impact on websites?

How Does Video Differ From Photos?

Humans have highly developed means of communicating with one another and understanding the world around us, and visual stimuli are only one element the brain will process. Nonverbal cues such as body language and environment are just as important, if not more so, when the brain processes information.

Video helps to satisfy the brain’s desire to understand more about something because it creates a sense of dimension, has movement, incorporates sounds and allows viewers to see nonverbal cues such as facial expressions and emotions. In contrast, static images present a subject in a narrow perspective, providing few additional clues to meaning.

Why Does Video Work?

You have probably learned about the different styles of learning, such as visual, auditory and kinesthetic. One of the reasons that video is such an effective medium of communication is that it utilizes both visual and auditory elements. Educators have long known that the most effective teaching styles incorporate both styles of communication, which is why a wise college professor will use lecture, reading and live presentations to teach concepts to students.

more8 Ways to Use Video Effectively on Your Website

You have probably heard that video is how to differentiate your website and establish a brand, but have you thought about where and how to use it? The beauty of using video on your website is that it is incredibly flexible and customizable. There are few rules. Unlike television, you do not have to fit your video into a certain block of time, so it is an enticing medium to express yourself and tell your business story.

If you are looking for some ideas on how to incorporate video into your website, consider trying one or more of the approaches below.

1. Use it as a personal introduction

The Internet is notoriously impersonal. Showing your face to the world and introducing yourself and what you do can be a powerful way to humanize your online presence. When an online visitor sees your face, he or she will make subconscious assessments that help to determine whether you are trustworthy and authentic.

2. Highlight and demonstrate products and services

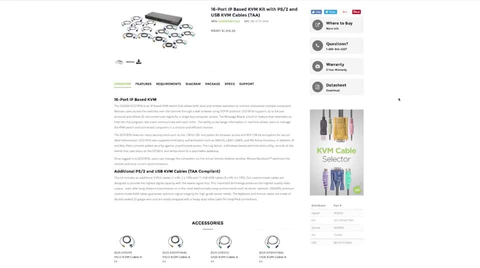

Video demonstrations help your website overcome the inherent disadvantage that comes with selling products on the Internet—the fact that a buyer cannot put his or her hands on a product. The two most popular approaches to showcasing products are to film a live demonstration or provide a 360° view. Live demonstrations tend to be the most effective approach because the viewer learns how to use the product.

moreCorporate Video SEO Benefits

Besides being valuable marketing pieces, corporate video production can help boost your company’s search engine optimization (SEO) efforts. Since video production for marketing purposes is largely about attracting more customers, gaining SEO benefits from your corporate videos is a no-brainer. Let’s take a look at some statistics to demonstrate another value that video marketing has for companies’ marketing efforts:

- YouTube is the second largest search engine, behind Google (and owned by Google), which means it ranks ahead of both Yahoo and Bing for user searchers. Placing your video on a company YouTube channel gives you additional opportunities to reach customers.

- A comScore study found that Website visitors stay on a page two minutes longer when it has a video. The average time visitors stay on a Website impacts its page ranking, which is essential for excellent rankings on Google. The faster visitors “bounce” from a site, the less relevant Google thinks the page is for the user’s search query.

- Brightcove found that videos posted to social media were shared 1200% more than both text and pictures combined. Increased shares can lead to increased likes and engagement with a company’s social media channel, which in turn improves traffic to the Website.

- Casey Henry at Moz states that having a video compared to just text increases the number of linking domains to a page by three fold. Because visitors prefer videos to simple text, they are more likely to link to the page. Referring domains is a critical element of high search engine rankings.

- Marketingland found that 62% of Google universal searches include videos, which are displayed at the top of the search results. With most searches showing videos, chances for ranking improve by using both text-based pages and video landing pages with descriptive text.

- aimClear found that video search results had a 41% higher click-through rate than text results. Not only are videos more likely to rank highly, but they’re more likely to generate traffic for a company’s Website.

National Video Production Company: Customer Case Study

National Video Production Services for Large Corporations & Companies

Senior Lifestyle operates senior living communities in more than half of U.S. states from coast to coast. As a result, their marketing and training divisions have a lot to handle not only on a local, community-specific level, but in standardizing operations and quality control across the portfolio. Operationally, a company could choose to let each individual community figure out their own marketing needs and hire local videographers, but the results may vary wildly. Strategically, most companies with numerous locations want to maintain certain high standards that are followed by each location. The goal is not only to assure similar quality and customer service from every location, but also to make sure the marketing goals align with corporate standards. A company like Senior Lifestyle is the perfect fit for our national video production company because we built JLB Media Productions to serve clients with video needs nationwide. For single-location businesses, choosing a local video company often makes sense especially for low budget productions. For a company like Senior Lifestyle with many dozens of properties spread across the United States that has high quality standards, a national one-stop video agency is the perfect fit.

moreBenefits Of Being a National Video Production Company Based In Los Angeles

Your business certainly has a plethora of options when it comes to choosing video production services. But how do you know which video production company is the best for your needs?

At JLB Media Productions, we have produced more than 1,000 professional videos for businesses across the country in 93 of the top 100 U.S. metro areas. Much of our success comes from being a national video production company based in Los Angeles.

Today, we’d like to help you better understand the benefits of being a national video production company based in Los Angeles and how it helps us best suit your company’s needs — no matter where you are in the United States!

Connections

There is no question that Los Angeles is the unrivaled location for video production and creative talent. While you may know Los Angeles for its major role in the production of television shows and movies, those areas are far from the only ones. Being a national video production company based in Los Angeles affords us the fantastic connections and relationships with the most talented professionals in the industry, many of whom also call Los Angeles home. Our network includes more than 100 talented videographers nationwide. These connections and the close proximity allows us to produce videos of exceptional quality, all while keeping the cost down for you!

morePros and Cons of In-House Video Production

A terrific-looking video is an extremely powerful marketing tool for your business. For one, it is a vital marketing element that you can utilize across platforms, from your website to your social media presence and beyond. But you only achieve successful videos through quality video production.

Corporate video production is just one of the many areas we specialize in here at JLB Media Productions, tapping into our wealth of experience and resources to provide our clients with the top-notch video production services they should expect.

However, we also understand that some companies may have the size and scope to consider bringing video production in-house, so today we broke down the decision into a basic pros and cons list. While there are benefits to each side, a business should carefully consider which route is best for the long-term success of the company. Besides, JLB Media is always here for you!

PROS

1. Volume

If you think your company is going to dedicate lots of time and resources toward corporate video production for any number of goals, then in-house video production might make sense. Once you have space, staff and equipment needed, you can make as many videos as you need.

moreFilming Commercials: Studio Versus On Location

With commercial filming, one of the first considerations with any concept is whether to film on location or in a studio. Of course, some concepts naturally require location filming, like cars driving through a city or in the country, for instance. Other concepts are more open-ended, like one set in a store or a living room. With lower budget commercials (i.e. not national commercials), a company will usually choose to film in their own store to save money. Likewise, finding a living room of someone’s house to film is much more cost-effective than building a living room set in a studio. There are advantages to filming in studios, though, and sometimes it makes the most sense overall.

The primary reason large production companies often choose to film in a studio versus on location is because of the greater control they have over every element of the production. Soundstages not only have standing permits, which means no special permit requirements, but they also have control over the sound in general of the area. Filming in a house somewhere requires permits from the city for street parking of numerous production vehicles, it has the potential to be interrupted by neighbors’ noise (barking dogs, car alarms, etc.), and it provides a more constricted environment for lighting.

moreHiring a Director for Corporate Video Work

The vast majority of corporate video work doesn’t require a trained or skilled director, primarily because there are no actors involved, but also because the budget doesn’t usually allow for it. In filmmaking, the director makes or approves all key creative decisions and works closely with department heads like production design, director of photography (cinematographer), and wardrobe, besides directing actors. Corporate video production often involves interviews and B-roll, neither of which specifically requires a creative director. In the corporate video world, you’re more likely to find videographers who double as the director on set, helping the interviews go smoothly, making decisions about which shots will look best for B-roll, and helping move the day along. The “one man band” mentality predominates, not because it’s the best way, but because it’s the cheapest way.

When does a corporate video need a director? The simplest answer to when hiring a director is required is whenever actors are brought aboard. While you can certainly take the risk and go without a director on set, letting the actors do their best and the videographer record whatever they do, it’s not advisable or highly professional. Not only are actors more comfortable with having a director who helps focus their performances, but a videographer may be equally uncomfortable trying to give advice or feedback to actors. They are not compatible or even related skills whatsoever. Videography is a technical skill highly dependent on camera knowledge, lighting temperatures, camera gadgets, and a general sense of painting with light. Directing involves tapping into inner emotional realities and bringing forth believable performances from actors as well as having an eye towards the bigger picture and how it will ultimately fit together.

moreSpecialty Filmmaking Tools for Corporate and Commercial Videos

In the world of big budget feature filmmaking, almost any type of specialty tool is available to capture the perfect shot. From specialty slow motion cameras to underwater housings to action cameras and car mounts, helicopter shots, and cranes, whatever a filmmaker can imagine, gear exists to help make his or her vision a reality. In the world of corporate filmmaking, a few tools are more likely to be considered for their relatively low impact on the budget but immense leap in production value. Though high budget commercial filmmaking includes all of the fun toys (techniques like “bullet time” from The Matrix and many early CG efforts were pioneered on commercials), corporate video work can incorporate a few fun tricks and tools as well.

The recent rise of action cameras like the most famous GoPro line allows filmmakers to capture exciting shots by putting the camera directly in the action. From helmet-mounted shots on a snowboarder or paraglider to inexpensive car-mounted cruising, the GoPro allows for Ultra HD filmmaking without heavy production costs. Any brand that wants to emphasize the excitement of their product in action can take advantage of something like a GoPro for capturing tough-to-film footage on the go. Creative videographers can find many ways to make use of GoPro cameras for filming story segments and product demos, so they need not be limited to outdoorsy products and extreme sports videos.

moreUsing Humor in Corporate Videos and Commercials

Comedy is a great way to engage audiences and hook them as part of an effective marketing video, but it also has pitfalls to avoid. Humor that one person finds hilarious, another person finds offensive. Especially in today’s world, the battle between PC social justice warriors and everyone else means many topics of humor are best left to late-night comedians and avoided by corporations. One need not look any further than Pepsi’s disastrous Kendall Jenner commercial, which was immediately pulled, to understand the dangers of comedy when mixed with politics. While politics is almost a definite subject to avoid, it’s not the only subject around which brands should tread carefully.

Playing around with gender comedy is potentially dangerous, especially when a brand assumes specific gender roles and the humor is based solely around such assumptions. For instance, “look at the silly girl trying to hunt with a big rifle” or “look at Mr. Dad struggling to take care of the kids” are just dated comedy tropes that simply don’t work in the 21st century. Not only will a small but substantial group of people oppose the depictions because of social justice reasons, but another group will be offended because you’ll make them feel inadequate in some way. A great stay-at-home dad shouldn’t feel ashamed or embarrassed by what he does for his family while watching your commercial, any more than a lady should feel less ladylike because she enjoys hunting or shooting at a range. Why alienate potential customers when you don’t need to use such humor to sell your brand?

moreViral Video Distribution Strategy

When trying to promote a viral video, of course you can only control its popularity to an extent, but you have to start the ball rolling, so to speak. Even the best videos need an initial push and a small base from which to grow. While some videos go viral seemingly randomly, others are carefully planned and can attain solid success levels through cultivating the right distribution strategies. As with any video, the normal rules apply of making sure you place the video on every network possible from Facebook to YouTube to Vimeo and your company’s home page, though your best viral results will likely come from YouTube and Facebook because of the massive group of users on each site.

When you’re trying to come up with a distribution strategy, first consider your intended audience, then consider where they are likely to congregate. If your video involves pets, for instance, you could probably find hundreds of pet-related Facebook groups and pages to post the video. Rather than spam other peoples’ pages, though, use diplomacy and charm to secure authorized posts. For instance, on our Mr. Formal “James Blonde” commercial, I wrote private messages to the administrators of several James Bond themed Facebook pages and each of them were friendly, even excited, to post the video to their page. They gave the project legitimacy by posting it themselves, as the group administrator. It took me barely any time to find the groups and compose the messages. Whatever your niche, you can find a bunch of interested groups on Facebook that will be receptive to your video if it’s well done, shareable, and perhaps funny.

moreCorporate Video Duration and Structuring

Most people have seen many marketing videos online, whether short commercials or longer product demonstrations, so intuitively most marketing professionals probably have a good idea about video length. At the same time, statistics help inform the proper structure and length of corporate videos using known data points. If most videos are between 30 seconds and 5 minutes, is there a sweet spot in duration? Does the length depend on the product or service being offered? Does the length depend on the type of video? Video production is a relatively expensive proposition, so you want to make sure when you commission and create a video that you’re getting the best value for your marketing dollars, which means tailoring the video length and structure to your audience.

Wistia, an online video platform, always publishes the best, most comprehensive research data about video statistics and engagement. They have a massive data set from which to draw, which means their information is highly actionable for marketing professionals. Through more than 1.3 billion plays of 564,710 videos, they found that the ideal video length was almost exactly two minutes. After two minutes, the drop-off in engagement was significant. For the purposes of their research, “engagement” means viewers who started the video and finished it. The best takeaway is the similarity between engagement numbers for a 30 second video versus a 90 second video, or any other length below two minutes. In other words, don’t worry much about whether a video is 70 seconds long or 90 seconds long; just convey the information you need and don’t obsess over a couple of seconds. Viewer engagement for videos under 2 minutes is about 70%.

moreCorporate Videos for Companies With Numerous Locations

Many companies have to plan their video strategy by thinking about whether they should produce general brand videos or produce specific videos for each of their locations. The decision may come down to budgeting, but if budget is less of a concern than practicality and marketing goals, then consider some pros and cons. If you run a business with numerous locations, here are some considerations:

- Is each location noticeably different, not just in layout but in service offerings? If so, you may want to advertise each location separately to emphasize its unique services. If each location is more or less the same, except for inventory and space, you are probably best served by a general purpose video for the brand and your stores as a whole. With nationwide department stores, they have no choice but to focus on the general brand as individual video marketing makes no sense.

- Are people familiar with your brand having multiple locations? If not, consider one combined brand video showcasing your different locations, educating consumers about the options they have for shopping your brand. You could dedicate just the last section of the video to your multiple locations.

- Does the style and character of each location feel different enough to warrant separate videos? In many cases, your service offerings may be similar (such as senior living), but the feel of each location is quite different. You may want to emphasize the uniqueness of each location without lumping them all into one video that ends up not feeling like any of the locations.

Fast Corporate Video Production

Typical turnaround time for most corporate video work is between 6 and 8 weeks, but you don’t have nearly as much time. You need a product launch video or a special company video to play at your conference in just a few weeks. Can you make a video production happen from start to finish in just a few weeks or are you out of luck? Luckily, if time is a concern, you can drastically shorten the process but only through careful focus, hard work, and the right production company. To put your video on the fast track, you need to shorten the pre-production process substantially and you need to have a rush edit of the footage or you won’t meet your deadlines. The actual production is the easy part, but the planning is where you need to save the most time.

In Hollywood, as well as probably the greater business world, filmmakers have a saying that you get to choose between two of these three options: fast, good, and cheap. You can have a high quality, cheap video, but it won’t be fast. You will be put last on the list of priorities and be at the mercy of someone else’s schedule because you’re not a well paying client. You can have fast and cheap, but the quality will suffer because you’ll probably be hiring a film student or amateur. What you’re looking to achieve is fast and good, but it won’t be cheap. You have to pay a premium to a production company to come in at the back of the line and push your way to the front, which requires paying more than their other clients. You have to obtain a rush edit of the video, which not only means overnighting the footage from wherever it was shot to the editor, but also paying enough so the editor can work overtime to complete a first edit. Whenever you tell a production company you need a video way faster than their typical time table, you’re asking them to undergo additional stress and risk that they won’t be inclined to do without financial incentive.

moreWhen to Pay for Two Cameras

Narrative feature films and high end commercials typically use only one camera, along with most dramatic scripted TV shows, so why would a corporate video need multiple cameras? The simple answer is that many corporate videos, especially event videos, are more similar in nature to reality TV, which often uses many cameras, even dozens of cameras, to capture all of the action. Though the vast majority of our shoots only have one camera, we have frequently used two for interview purposes and occasionally relied upon several shooters at events as well. Hollywood feature films, except for during action sequences, often avoid using more than one camera because the lighting is specifically set up for a single camera at a designated location. With corporate interviews, though, the subject isn’t moving and the lighting can work perfectly fine from two different angles if arranged carefully.

One of the key benefits of filming an interview with two cameras is the ability to cut in and out of different takes more readily without cutting to B-roll. If you have a single camera interview and the interviewee flubs a line half-way into the take, you either have to use an entirely different take, or cut to a B-roll shot, then back into the second half of a correct take. With multiple camera angles, you can cut out of the take from Camera A and into a better take from Camera B flawlessly. The ability to zip around in editing makes for smoother interviews in many cases, especially when the B-roll is limited or when the client wants more focus on the interview itself.

moreProducing Corporate Videos

Corporate video work at lower budget levels is not much of a producing challenge compared to feature films or even short films, but making sure the process runs smoothly is part of what makes a production company worth hiring. Producing a video production of any kind involves several basic elements, the first of which is an examination of the script or concept that is the basis of the whole project. In the filmmaking world, a script is like an architectural blueprint that helps guide the process, but in corporate videos a script is often missing, so how do you proceed? Much more so than narrative storytelling, corporate video producing starts with a finished idea and works backwards. In other words, a client wants a video similar to the one completed for ABC Company, so the producing process works by figuring out the similarities and differences between an already-produced video and the current project.

If a client expresses interest in creating a business overview video to post to their Website, the production company asks a series of questions that are relevant first to budgeting then to producing the video itself. How many people will be interviewed? Where will the interviews take place? Can all of the interviews be shot on the same day? Will B-roll (additional video elements that play along with the interview commentary) be recorded at the same location or in multiple locations? After a discussion with the client, we gather the details: 4 interview subjects from the company, filmed in one location at their corporate office, with various B-roll involving other employees and business around the office. Only part of the full picture comes together from the previous information, though.

moreStoryboarding Videos

Though not necessary for the vast majority of corporate video work, storyboarding is common practice in commercial video production. In the commercial world, storyboards are usually referred to simply as “boards” and are a way to demonstrate visual ideas to the client for approval before a shoot occurs. Because of the immense amount of money spent on commercial production, the advertising agency wants to make sure the client fully understands and signs off on any ideas before hundreds of thousands of dollars are spent on producing a finished commercial. As part of the process, once the general concept for the commercial is approved, boards are created to show a shot-by-shot look at the flow. Understanding the value of storyboards is a good way to understand whether they are the right way to proceed for smaller budget corporate video work or general commercial work.

Storyboards have multiple purposes and uses, depending on who is reviewing them and who they are intended to impress. When designed for clients, they are primarily intended to represent a concept visually for fuller understanding of the flow of the commercial or corporate video. Not everyone can read a concept on paper and visualize how it will look roughly when shot, so being able to create storyboards allows everyone to be on the same page without any big surprises. Even on more limited budgets, storyboards can be valuable to communicate information quickly and avoid unpleasant surprises down the road.

moreHow To Use Videos Effectively During The Holiday Season

For many people, the holiday season is a special time of year. We get nostalgic, we work to reconnect with loved ones, and our hearts are just a little more receptive. To effectively use videos during the end-of-year holiday season, keep the following in mind.

Start Early!

Whether it’s related to Thanksgiving, Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanzaa, Diwali, Winter Solstice, New Year’s Eve, or any other winter-time holiday (or summer-time festivities, if you’re south of the equator), it’s important that you launch your holiday season video production push early. Once Halloween is over, everything moves quickly. Plus, a lot of employees are gone, which can slow down production. The earlier you start, the better … but at the same time, it’s never too late. Get started today! Just be realistic with your schedule. You may still be in time for the holidays, or you may want to aim for the New Year.

Get Creative

As we’ve mentioned before in previous posts, people love stories. During the holiday season, you have the opportunity to get creative and craft stories through your promotional videos that touch the heart and lift the spirit. It’s a time when you can have fun with your videos while remaining culturally sensitive and respectful to your audience. Whether you have thirty seconds, two minutes, or an hour or more of video time to work with, you can tell a heartwarming story to share your brand or uplift your employees.

more5 Ways Technology Companies Need to Leverage Video Production

If you’re a marketer or an executive at a technology company, you need to know that leveraging your video production efforts is in your company’s best interest. Here are five effective ways to accomplish this.

Product Demo

Your company will benefit from videos that showcase your products and services. If you offer a complex product with features the end-user may not be aware of, a product demo video is a must. You can convey a great deal of information quickly and clearly through a visual demo.

With a product demo, you can accomplish the following:

- Highlight features that make your product stand out;

- Show how your product is better than what competitors offer;

- Generate excitement for your brand;

- Instruct the user on how to use a specific product; and

- Offer solutions so viewers can see why they need your products.

Your demo video is your chance to sell your product by highlighting the best features and providing enough technical info without overwhelming the viewer. It lets viewers understand why they need this, and how to get started. In other words, it’s the perfect launching point for anyone interested in your product.

moreA Marketer’s Guide to Creating a Software Demo Video

The other day, I downloaded an audio enhancement software program to use the trial version. However, without much support on how to use it, I quickly found myself frustrated, and instead of purchasing the software, the company link sits in my Bookmarks folder in marketing limbo.

Sound familiar?

If you’re worried that your software product might be suffering a similar fate, it’s a great opportunity for you to create a software demo video. Done well, this will keep your customers engaged, show them a vision of what they can accomplish, and get them to understand the value of what you offer.

In this post, I’ll cover how you can create high-quality software videos, enhance your customers’ understanding of your software, and get more conversions.

Step 1: Choose a video production company

If you have an internal video department, this step might be as simple as submitting a video request, but if you’re going to outsource this job, you’ll need to take into account a number of different factors to ensure that you’re getting the highest quality work for the best price. We recommend that you ask the following questions to any potential video production services provider you’re considering.

moreInsider Tips: Pitfalls to Avoid When Choosing a Video Production Company

Avoid Choosing a Company with a Limited (or Inexistent) Portfolio

This is no time for amateur hour. Your corporate videos must be professional and polished, and they need to communicate the right message while reflecting your brand in a positive light. Each video needs to make an impact, and it has to be memorable, with the key points you want to convey getting across to viewers.

It takes a certain level of experience plus a mix of just the right technical, creative, and business skills to produce corporate, marketing, and promotional videos that exude a high degree of professionalism while being entertaining and innovative. A video production company with a limited portfolio, or a company that has no samples to show, is not the right choice. The risk of spending a great deal of money and ending up with poor results is just too great.

The Production Company Shouldn’t Skimp on Creativity

Even if your promotional video is a marketing tool meant to promote your brand and gain a larger following, the creative factor is still important. The video production company you hire needs to work with talented writers, producers, videographers, choreographers, musicians, and other professionals to develop a video that’s more than just a sales pitch. The more creativity that a corporate video production company can infuse into your videos, the more interested your audiences will be in the messages you’re trying to get out. Never skimp on creativity.

moreVideo Production Inspiration For Your Marketing Campaigns

A little bit of cinematography magic will make your promo videos far more engaging and memorable, greatly enhancing your marketing efforts.

Don’t Be Afraid to Get Creative

When it comes to marketing campaigns, video productions can convey a wealth of information in a short time. Here’s an important thing to remember: if you’re having fun making the video, chances are good that viewers will have fun watching it, and that element of fun will help make your message stick. So let your guard down, and start getting creative!

It Begins With A Story

Your promotional video has to tell a clear story in a succinct format. You only have a few seconds or minutes to get your message across, so the challenge is to use that brief time to visually convey a story viewers will associate with your brand. Start by listing the main points you want to convey, and remember that less is more. Your main message should be woven throughout the entire promo video, and you can add one or two supporting points, but keep things simple. Try not to stuff too much information into one production. Stick to the most important takeaway points, and then tell a story that highlights these specific details. You can have the most polished video ever made, but if it doesn’t present a cohesive story that hooks viewers in, it’ll be quickly forgotten. Well before writing and shooting any marketing videos, brainstorm possible ideas and outline plot lines for inspiration.

moreCommercial Television Production Costs

While the cost of commercial television production is widely known to advertising agencies and production companies, most outside marketing professionals, especially for small to mid-sized businesses, have very little idea about the costs involved. As with any advertising, the range is enormous between the lowest budget and highest budget examples. At the lower end, many or even most cable networks will offer “free” commercial production if a business purchases a certain volume of TV advertising. They build the costs of producing the commercial into the overall package pricing, which also results in almost always laughably amateur hour productions. The difference between typical local TV ads and national ones is like watching an NBA player take on a grade school kid. Examining the true costs involved in different types and levels of media production is a great place to start when looking at how to budget properly.

For a local TV commercial production, the business is often of local interest only, like an HVAC company, a dental office, a furniture store, or a restaurant. The biggest difference viewers will notice is the focus of local commercials on offering “deals” or mentioning pricing, specific services, and information. Put simply, local commercials create awareness, whereas national commercials reinforce brand power. Viewers probably don’t know about John’s HVAC, so the local commercial focuses on their commitment to service, quality, and affordability. Everyone knows Coca Cola, so the national commercial is just a reminder to “open happiness.” The biggest difference is creativity, which also impacts cost.

moreWhat Separates Low Budget Corporate Videos from High Budget Profile Pieces

Many of our clients think of JLB Media Productions as a great budget option to deliver quality, affordable corporate video production services for their businesses. While we enjoy the opportunity to produce all types of corporate work, we also like to emphasize that our creativity is limited only by the budget, not by our experience. When you think of a restaurant chain like Olive Garden, you probably think of solid, affordable Italian food, nothing special, but not a bad option for a regular meal. When you think about Safeway, you maybe think of a regular, ordinary grocery store that will meet your needs most of the time, but nothing fancy like Whole Foods or Trader Joe’s with specialty items and gourmet selections. Every company has its niche, which they either define intentionally, or fall into unintentionally, but with a video production company the key ingredient is creativity.

If a video production company has just one staff member, such as a camera operator who also edits, the company may by design be more tailored to crafting straightforward videos without a lot of bells and whistles. You wouldn’t hire Joe Blow Productions to create your nationwide commercial campaign, for instance. You would hire Joe Blow Productions for your internal company videos, though, because he’s affordable and delivers solid results for the audience. At its essence, though, film is a very different business than grocery stores or restaurants. A grocery store could rebrand itself and change a bunch of their suppliers, reconstruct their stores, and focus on a new demographic. A restaurant could change directions and offer alternative foods, redoing their ingredient lists and recipes. In both cases, the businesses have to alter everything they do to serve a different demographic or need.

more360 Virtual Tours Vs. Professional Video – Why Successful Businesses Choose Web Videos

Making your visitors navigate through fish-eye pictures of model apartments may seem like a nice idea in creating Website interactivity, but it can also be an exercise in frustration for potential customers who just want to push play, sit back, and observe. When you let your visitors choose how they see your community or business, you give them the opportunity to become frustrated, bored, or worse yet, confused. When you have a video, you have full marketing control not only of how information is presented but the manner in which it is displayed. For instance, good use of music can strike an emotional chord with viewers that a fish-eye photo of a room simply cannot, no matter how many times it spins around.

Videos also provide a lot more options, from voiceover and music at the simplest end to actors and spokespeople at the higher end. Are you selling an apartment room, a hotel room, or a building, or are you selling a community, an experience, and a way of life? People are not moved by simple facts or floor plans, but by attempts to form an emotional connection to the material. Compare a rousing speech to a pamphlet, or a beautiful symphony to a sheet of music, or a stale 360 image that first came on the scene when we all used dial-up modems to a beautiful video that shows your company understands its audience.

moreCorporate Video Production on a Budget

As with most video production companies, we have common inquiries from startup companies or individuals who want to create nice videos for tiny budgets. Many times, we have to turn away the smallest potential clients because we cannot do justice to their video for the funds they have, but we always try to come up with creative solutions that could work to create a professional video on a small budget. Low budget work doesn’t have to mean low quality work, but managing expectations is important as is coming up with a proper concept. The biggest issue is when companies want to create a Hollywood-style video on a smaller budget, because many times it will just become hokey or simply be impossible to execute, often leaving the company with no video at all.

One of the best recommendations we have made for our clients is to consider a video using voiceover, stock footage, and brand / product photos they have, sometimes in combination with motion graphics templates we already own or that can be acquired inexpensively. Many motion graphics templates look fantastic and high-end, so just because they’re not “custom made” doesn’t mean the final product has to suffer. By focusing on clever text effects, motion graphics, stock footage, stock music, and voiceover, a company can eliminate the production portion of the video production and achieve significant cost savings while still producing a professional, informative video that relies on creative editing and messaging to succeed.

moreCost Considerations and Budgeting for Video Production

With video increasing search engine rankings and giving a massive boost to front-page Google rankings for companies and their products and services, most companies understand the need for effective video marketing. While videos can play a key role in an overall marketing strategy and be distributed to numerous locations from Facebook and YouTube to the company’s Website, companies have to ascertain how much money can be allocated to video production to achieve the desired result. Most importantly, how much do you need to spend to have a professional video that meets your marketing goals and yet leaves you money left over for other pressing needs? The cost of any video production is based on a number of factors, but best seen as a series of three stages: pre-production, production, and post-production.

Pre-Production Planning

The expenses incurred during pre-production are based around taking a concept or a video idea to a finished plan for production. Pre-production can be as simple as picking a date for the filming, creating a schedule for the day’s filming, hiring a videographer, and dealing with some contracts and paperwork. It can also be much more sophisticated and time-consuming, involving securing locations, crew, talent, and writing a script or detailed outline. The more work a production company needs to do during pre-production, the greater the cost of the video not only because of the time expended but because a large and in-depth pre-production means a larger production as well.

moreCreating Videos to Honor Top Employees

Though corporate video production usually centers around specific marketing goals or sometimes training videos for internal use, another type of video production is focused on creating a better employee culture and honoring top employees through a video. Though on the surface an employee award video may seem a questionable use of scarce marketing resources, the benefits can be much more substantial than initially envisioned. Not only can an employee award video instill loyalty in top employees, increasing retention of talent, but it can instill a company-wide feeling that top management notices and cares about the contributions of its employees. The video can also be crafted as a pseudo-training video for what types of strategies and behavior lead to great results, then shown throughout the company to improve performance.

A typical employee award video need not be expensive or complicated, but rather a simple way to honor the hard work and dedication of your best employees. Ideally, the shoot should be scheduled on a day where the employee can be shown performing regular tasks to capture some solid B-roll, then be available for an interview afterwards. Other employees who work regularly with the award-winning employee can provide additional commentary, speaking about the person’s disposition, hard work, and winning personality. An additional bonus is obtaining interview commentary from people who the employee serves, whether its regular customers, vendors, or residents of a care facility.

moreDeciding Between a Professional Spokesperson or Company Representative

In creating corporate videos, companies are often faced with the decision of whether to hire a professional actor or actress to serve as a spokesperson or select one of their employees to deliver the information and be the “face of the company” at least for one video or video series. Each path has its advantages and disadvantages, which means deciding between the right option depends largely on the company’s marketing goals, budget, and preferences. Taking a look at each option and the benefits and drawbacks is a good starting point for helping you come to a decision about which path serves your needs best.

Pros and Cons of Company Representative

With a company representative featured on camera, you have the advantage of a knowledgeable professional who can speak naturally about the product or service. A company representative like a marketing head probably has delivered many such speeches in the past either informally at networking events, to potential customers, or friends and family or in more formal settings like presentations and client conference calls. Their knowledge and expertise makes them ideally qualified for delivering information, at least on paper.

moreGreen Screen or White Screen in Corporate Video Production

Several of our clients have asked about shooting a spokesperson against a white screen or a green screen, but many people aren’t really sure which one they want or for what reasons. Numerous Web videos, especially informational ones, are filmed against white backgrounds not only for the simplicity of production but also for creating a more focused visual field. Filming against a green screen (or blue screen, in the past) is an entirely different type of process with different end-goals. Knowing which setup makes the most sense for your corporate video depends largely on need, so let’s take a look at both processes and outcomes.

White Screen Videos

Using a white background or white screen allows the spokesperson or actor to be the sole focus of the composition, often removing any possible distractions present in an office setting or a heavily production-designed desk. Shooting against a white background has added benefits, though, in allowing for adding text elements, motion graphics, and even B-roll fields to the sides of the actor. Shooting against a white screen is often the best way to provide flexibility in delivering additional information in post-production because it gives the editor a lot of space with which to play.

moreIdeal Videographer for Corporate Work: Finding The Right Professional

Perhaps the most important aspect of a successful corporate shoot is the videographer who shows up to gather the footage and record the audio. All of the planning that the production company does before the shoot, all of the paperwork, all of the client’s time and planning, and all of the effort that an editor goes through to create a finished video are meaningless if the video quality isn’t good or the audio sounds distorted and poor. Selecting the right videographer for a job is not as simple as just finding “the best” shooter, but rather finding the perfect fit for the budget level and for the project, which is where a knowledgable corporate video production company shows its value.

The first consideration for selecting a videographer should be their creative eye and their diverse set of skills. Can the videographer manage a nice variety and balance of pans, tilts, zooms, slides, and perhaps handheld work that looks professional with smooth motion? Does the videographer have a great eye for framing and focusing his attention on the most visually interesting aspects of a location and its subjects? Do the interviews sound crisp, clear, and look well framed? A great videographer is able to deliver visually interesting footage of almost any location, regardless of what they are shooting. By contrast, an unimaginative shooter will plop the tripod down at random, press record, and be satisfied with mediocre results. Never hire someone whose work doesn’t grab your attention immediately. After watching thousands upon thousands of reels and work samples, a professional producer can identify quality work within thirty seconds or fewer.

moreDo I Need 4K Corporate Video Production?

Without working in video production, many consumers and clients are confused by terms thrown out in the film industry like UHD (Ultra High Definition), 4K, and HD. Because of different standards and even inaccurate labeling, most people aren’t really sure of the difference between each label and what they really mean. On a practical level for corporate video production, should marketing professionals care about the newest video standards like 4K? Though the answer is more complicated than a simple yes or no, the bottom line is most clients won’t benefit from having their videos shot in 4K.

Even the label “HD video” can be misleading because officially, HD is defined as either 720p or 1080p, where the number represents how many vertical lines of resolution exist in the image. As a broadcast standard, the overall picture resolution is 1280×720 of progressively (p) scanned lines. Although 720p counts as HD resolution, few professionals take such a low resolution seriously now for acquisition. “Full HD” refers to 1080p, or a resolution of 1920×1080, which almost every modern camera can record. Sites like YouTube count 720p as an HD resolution, but for playback online, especially on mobile devices, 720p is a perfectly suitable HD format.

morePopular Video of the Week: Sliders 4 Ways

With the ease of sharing videos across social media networks and the Internet as a whole, every week sees the rise of new highly shared video content. Keeping an eye on the trends is a solid way to see what works, what people share, and how videos go viral. Even if a video seems unspectacular or not related to marketing in general, keeping an eye on popular videos is a good way to make mental notes about what people are likely to share. Last week, BuzzFeed’s Tasty posted a video of how to make sliders in four different ways that has received more than 80 million views on Facebook.

The video is a simple tutorial or “how to” for cooking, sped up in post-production with music and text added, that appeals to cooks everywhere. It contains several recipes and shows how to execute them, making the process look easy to do for anyone with basic culinary skills. How is the video relevant to marketing or what can we learn from the massive popularity of a seemingly simple video? Let’s take a look:

- The video would be inexpensive to create, involving one camera, basic setups, and mainly a few hours to do the demonstrations featured. Editing time would be fairly minimal to average.

- The appeal of the video is widespread because everyone likes to eat and many people either cook regularly or would like to learn more about cooking.

- The video is short, running less than two minutes, so the likelihood of people watching the majority of the video or all of the video is high.

- The video has numerous elements that could be used in similar fashion by a variety of companies. A company that sells bread rolls could keep in mind the massive video view total and produce a similar branded video with more information about their product and why their bread rolls make a perfect solution for sliders. A grocery store chain could create a similar video and mention that all of the ingredients can be found at their grocery store affordably, in high quality, and at a location near the viewer. Any manufacturer of individual ingredients like a meat producer could feature their own products in such a demonstration, cleverly disguised in a “how to” video so that it doesn’t feel like marketing, but like helpful information to cooks everywhere.

Reduce Costs Through Effective Training Video Production

Most corporations, especially medium to larger businesses with numerous physical locations, have frequent turnover throughout the company. While turnover is normal, it also leads to increased training costs and frequent frustrations with new employees not properly following the company’s standards, practices, and values. Training new employees is both expensive and time consuming, but training videos can help companies gain an edge in company-wide education and training at a fraction of the cost of in-person physical training. Sending key employees to numerous facilities repeatedly becomes expensive and unrealistic, especially given the greater responsibilities and higher-value tasks that key employees often have to undertake. Having a series of training videos for employees to view allows top employees to pursue their everyday activities while also educating new hires in the company’s proper standards and procedures without leaving the corporate headquarters.In days past, training video production could be both expensive and just as time-consuming as in-person training, but with proper coordination and selecting the right company for the job, training videos can be affordable and effective. Companies have a variety of tools at their disposal with training video production, not just live-action videos and staged scenes, but animation-driven pieces, screen capture videos, and simple demonstrations by key employees that need not cost tens of thousands of dollars to develop. Even better, as standards and practices change and evolve, training videos can continue to be updated without being completely recreated for a fraction of the cost and frustration of sending key employees on company-wide road trips.

moreRefreshing an Old Video or Filming a New One

Years ago, your company commissioned a great video, but enough has changed about your company or about the product or service in question that you know you need to update the video or redo it completely. Reasons for redoing a video differ, but often are necessary because of remodels, new employee hires, updated product lines, new service offerings, a change in company marketing strategy, and unhappiness with significant elements about an older video production. As with any company, though, your marketing budget is tight and the last video was expensive. Should you refresh the video or redo it completely? Each path has pros and cons, but considering all of the factors involved will help you make the right decision for your company.

The obvious first question — though it still has to be mentioned — is whether your current video is professional, well produced, and overall a solid piece of work. Take a well shot apartment tour video, for instance, perhaps the lobby has been updated, paint refreshed, and landscaping improved, but many of the areas like the fitness center, model units, and exterior overall look the same. Sending out a videographer for two hours to gather updated shots of whatever has changed and integrating the footage into the existing video makes perfect sense as long as you have the original raw footage, editing file, and other data needed for the refresh. If you are still working with the same production company, maybe they have the files still, making the refresh easier and less costly.

moreSetting Up the Perfect Interview

The key to many great corporate videos is great interview footage, which is a mixture of the right subject, the right setting, the right framing, and most importantly proper audio. Interviews are the toughest and most important part of most corporate video shoots because the people being interviewed are not trained professionals, the locations are often not ideal from an audio perspective, and most corporate videos lack the budget for a production designer let alone a production design department with set dressers and rented items to beautify a space. Though challenging, like most aspects of corporate video production, gathering quality interviews is largely a matter of careful planning.

The first critical element to obtaining great interviews is selecting the right subjects. Our company has shot hundreds of videos with interview commentary and the best ones with the strongest quotes are always the videos where our client chose great subjects. As with film production in general, much of the battle is won during pre-production, not only in selecting the right interview subjects but in crafting the right questions. To create a list of the best possible questions, first think about what answers or comments you want in the finished video.

moreThe Importance of Telling Your Business Story

There seems to be a lot of talk about the importance of branding, but little substance about what comprises a brand. Ultimately, perceptions define a brand. Essentially an extension of the human dynamic of relationships, branding is about feelings, trust and respect. Telling the story of your business is one of the most powerful ways to stir emotions, build trust and immortalize your brand.

What Exactly is a Business Story?

Every business has a story, which includes:

- A company’s roots and history

- Track record

- Values

- Good deeds

- Contributions to the world

- Successes and failures

Knowing which of these aspects to highlight is part of the challenge of branding. A business story need not be all “rainbows and butterflies,” but in order to be an effective branding tool, it needs to be positive overall and most importantly, relatable.

Why do Business Stories Matter?

People have countless choices for products and services and they are increasingly cognizant of how a business can influence the world for good and bad. Customers want to know they are supporting something positive and meaningful; they want to spend money with businesses they can trust to be virtuous.

moreThe Power of Video to Move Products

Nobody wants to spend more money on a video than necessary, but nobody wants a video to look cheap, either. Fortunately, modern technology and old-fashioned planning allow for the creation of nice, professional videos even on small budgets. In days before digital filmmaking, options for low-budget filmmaking were limited and looked cheap, making a brand or company look cheesy in the process. In modern corporate video production, the talent costs more money than the gear, which leads to potentially great results when talented professionals can also work efficiently.

Pre-Production Scheduling and Planning

The key to low budget video production is to minimize the time that talented, expensive professionals need to spend on the video, which means maximizing the time invested in pre-production before even hiring a corporate video company. For a company overview video, for instance, know the basic message of the video, who will provide interview commentary or what the voiceover script will include, and which B-roll elements need filming. A tight, detailed schedule allows for minimal production time and thus saves costs for the most expensive part of the process. A low budget company overview video can be shot in as few as three hours if planned accordingly.

moreTips for Making Low Budget Videos Look Expensive

Nobody wants to spend more money on a video than necessary, but nobody wants a video to look cheap, either. Fortunately, modern technology and old-fashioned planning allow for the creation of nice, professional videos even on small budgets. In days before digital filmmaking, options for low-budget filmmaking were limited and looked cheap, making a brand or company look cheesy in the process. In modern corporate video production, the talent costs more money than the gear, which leads to potentially great results when talented professionals can also work efficiently.

Pre-Production Scheduling and Planning

The key to low budget video production is to minimize the time that talented, expensive professionals need to spend on the video, which means maximizing the time invested in pre-production before even hiring a corporate video company. For a company overview video, for instance, know the basic message of the video, who will provide interview commentary or what the voiceover script will include, and which B-roll elements need filming. A tight, detailed schedule allows for minimal production time and thus saves costs for the most expensive part of the process. A low budget company overview video can be shot in as few as three hours if planned accordingly.

moreUsing Video Case Studies to Boost Product Sales

Case studies have long been a favorite marketing tool for businesses in building trust in their brand and increasing sales to new customers. Whether selling a product to consumers or businesses, video case studies provide a great way to demonstrate the benefits of your product quickly and in a tangible rather than abstract way. You have the opportunity to show real people talking about your product, why they wanted or needed it, and why it was the best choice for them. Who better to help market your products than satisfied customers?

People enjoy watching stories more than they enjoy watching marketing-heavy commercials, so take advantage of what people enjoy watching by creating a case study video that feels like a story. For instance, a small business owner may start with discussing what their business does, what problems or challenges they face, and how your product helped them solve the issue. A company like Nike may feature a consumer training for a marathon who wanted to find comfortable, effective shoes and clothing to help their efforts. The video could start with the subject talking about their training efforts, the challenges they faced in finding the right supplies, and how Nike provided the perfect solutions that maximized their training.

moreVideo Production Company Versus Video Agency

On the hierarchy of companies that create videos, the order usually starts at the top with marketing agencies, then production companies, and finally one-man-band type of operations. In the latter example, one person shoots the video, edits it, and manages all elements of creation themselves. Understandably, the more people who are involved, the more expensive the video. Nonetheless, with highly specialized talent involved from pre-production through post-production, expensive marketing agency videos often yield the best results if a client can bear the steep price of entry. Meanwhile, an average video production company offers some specialization, such as a professional cinematographer and a separate editor, along with limited creative guidance. Besides the traditional three types of video producers, I would argue for a fourth type better known as a video agency with greater creative capabilities and oversight.